Adolfo Kaminsky’s talent was as simple as it gets: he knew how to get blue ink off the paper that was supposed to be impossible to get off. During World War II, though this skill saved the lives of thousands of Jews in France.

As a teenager working for a clothes dyer and dry cleaner in his Normandy town, he had learned how to get rid of these kinds of stains. When he was 18, he joined the anti-Nazi resistance. Because of his experience, he was able to change official French ID and food ration cards that had Jewish-sounding names like Abraham or Isaac to names that sounded more like those of French people who were not Jewish.

Jewish children, their parents, and other people were able to avoid being sent to Auschwitz and other concentration camps because of the fake documents. In many cases, they were also able to leave Nazi-controlled areas and go to safer places.

At one point, Mr. Kaminsky was asked to find 900 birth and baptismal certificates and ration cards for 300 Jewish children in institutions who were about to be rounded up. The goal was to trick the Germans until the children could be sent to families in the country, convents, or Switzerland and Spain. He had three days to finish the project.

He worked nonstop for two days, staying awake by telling himself, “In an hour, I can make 30 blank documents. If I sleep for an hour 30 people will die.”

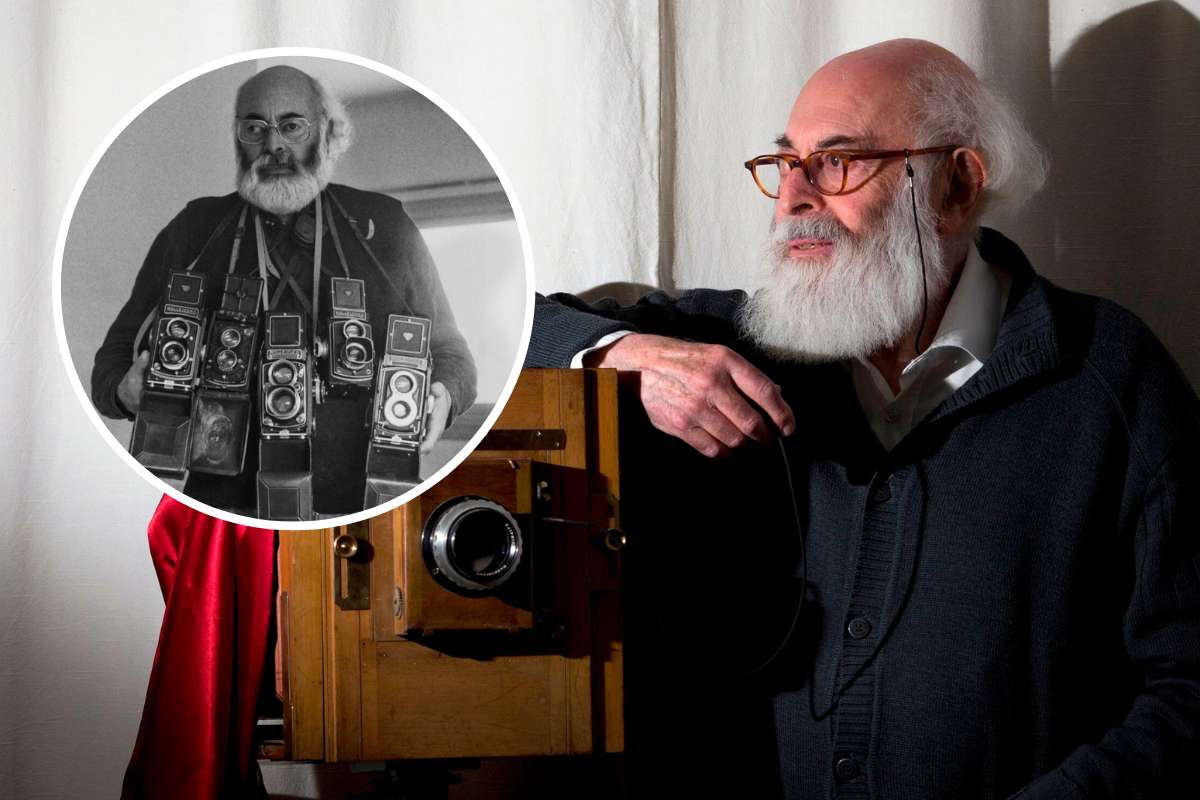

Sarah Kaminsky, his daughter, said that Mr. Kaminsky died on Monday at his home in Paris. He was 97. His story sounds like it came from a spy book.

Adolfo Kaminsky’s talent was as banal as could be: He knew how to remove supposedly indelible blue ink from paper. But it was a skill that helped save the lives of thousands of Jews in France during World War II. https://t.co/dVK3FPPmyk

— New York Times World (@nytimesworld) January 9, 2023

Mr. Kaminsky, who went by the name Julien Keller, was a key member of a Paris underground lab whose members all worked for free and risked a quick death if they were found out. They used names like Water Lily, Penguin, and Otter and often made up documents from scratch.

Mr. Kaminsky learned how to make different typefaces in elementary school when he was in charge of the school newspaper. He was able to copy the typefaces used by the authorities. He pressed paper so that it, too, looked like the kind used on official documents. He also photoengraved his own rubber stamps, letterheads, and watermarks.

Other resistance groups heard about the cell, and soon it was making 500 documents a week on orders from partisans in several European countries. Mr. Kaminsky thought that the underground network he was a part of saved 10,000 people, most of whom were children.

After Paris was freed, Mr. Kaminsky went to work for the new French government. There, he made up documents that allowed intelligence agents to sneak into Nazi territory and get information about the death camps.

He kept making fake documents for 30 years after the war, helping rebels in Palestine, which was under British rule, French Algeria, South Africa, and Latin America. During the Vietnam War, he also made fake papers for people who wanted to avoid the military draught.

“I saved lives because I can’t deal with unnecessary deaths — I just can’t,” he told The New York Times in 2016. “All humans are equal, whatever their origins, their beliefs, their skin color. There are no superiors, no inferiors. That is not acceptable for me.”

The Opinion section of The Times made a documentary short about Mr. Kaminsky called “The Forger,” which won an Emmy Award. In the early 1970s, Mr. Kaminsky stopped being a forger and started making a living as a photographer and photography teacher in Paris. He took pictures of romantic scenes like lovers sitting on a bench at night, far from the chaos of war.

He was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on October 1, 1925. Salomon Kaminsky and Anna (Kinol) Kaminsky were both born in Russia, but they met in Paris in 1916. His mother had to leave Russia because of the pogroms, and his father worked for a Jewish Marxist newspaper. When the Bolsheviks overthrew the czarist government, France kicked out people who supported the new government. The Kaminskys fled to Argentina, where they had two more sons.

Have a look at:

- Trump Announces Diamond’s Death: Lynette Hardaway Dies at 51

- Jim Hutton’s Cause of Death is Now Revealed: How Did He Die?

By the early 1930s, the Kaminskys were able to go back to France and live in the town of Vire in Normandy. Adolfo quit school when he was 13 to help an uncle run his market stall, but the uncle was too bossy, so the boy quit and went to work in a factory that made instruments for aeroplanes.

In 1940, the Germans went into France. They took over the Normandy factory and fired everyone who worked there who was Jewish. Adolfo needed a job to help support his family, so he answered an ad for an apprentice dyer at a business that turned military uniforms and greatcoats into clothes that civilians could wear. The owner, who was a chemical engineer, taught him how to change and take away colors. Adolfo learned how to get rid of even the toughest stains.

He became so interested in chemistry that he worked as a chemist’s assistant at a butter-making dairy. To figure out how much fat was in the cream that farmers brought, the dairy would put methylene blue in a sample and wait for the lactic acid in the sample to break down the color. That’s how Adolfo found out that lactic acid was the best way to get rid of ID card ink made with Waterman blue ink.

In 1941, the Kaminskys were arrested and sent to Drancy, an internment camp near Paris that was a stop on the way to the death camps. Because they were from Argentina, they were freed after three months.

RIP Adolfo Kaminsky. Joining the French Resistance aged 17, he fabricated papers which saved the lives of thousands of Jews. He later made fake IDs and money for Algeria’s FLN and people fighting regimes in Greece, Spain, and Latin America, as well as Vietnam draft-dodgers pic.twitter.com/sZmcwKoqNN

— David Broder (@broderly) January 9, 2023

But the family soon worried that the passports wouldn’t protect them anymore. At age 18, Adolfo was sent to the French underground to get documents that would make it look like they weren’t Jews. When the agents of the resistance found out about his skills, they hired him.

“Adolfo Kaminsky: A Forger’s Life,” a memoir written in his voice by his daughter Sarah Kaminsky and published in English in 2016, tells the story of how he started working for the resistance in earnest when he found out that his mother had been killed on a train coming back from Paris, where she had gone to warn her brother that he was going to be arrested.

He was so angry that he did several acts of sabotage, like putting chemicals on railway equipment and transmission lines to make them rust and break. He said he was looking for revenge and needed “comfort for his sadness.” “For the first time I didn’t feel entirely impotent,” he said.

It was dangerous to fake documents. Once, a police officer stopped him on the Paris Metro and asked to look in his bag, which had blank identity papers and tools for making fake ones. Mr. Kaminsky had to think quickly, so he told him it had sandwiches and asked if he wanted one. The officer went on.

Sad news of the death of Adolfo Kaminsky, the heroic forger who used his skills to save thousands of Jews during the Holocaust and to help the FLN and other national liberation and antifascist groups, as well as those dodging the draft in imperialist wars. Rest in power✊ https://t.co/2M7UNYVcb3

— Dónal Hassett (@donalhassett1) January 9, 2023

Several of Mr. Kaminsky’s underground friends were caught and killed, and the stress of doing such hard work for hours on end caused him to lose sight in one eye.

In 1950, he married Jeanine Korngold, but they split up in 1952. He married Leila Bendjebour in 1974. In addition to his daughter Sarah from his second marriage, Mr. Kaminsky is survived by his wife, their two sons, Atahualpa and José-Youcef, his daughter Marthe from his first marriage, his sister Pauline Gerlich, and nine grandchildren. Serge, one of his sons from his first marriage, had a heart attack and died in 2021.

In a talk she gave in Paris in 2010, Sarah Kaminsky talked about the first time she saw what her father did for a living. She said that she had gotten a bad grade in school and needed her mother’s signature to show that she had told her parents. So she lied about it.

Her mother saw right away that it was a fake and told her to stop, but her father just laughed. “But really, Sarah, you could have worked harder,” he said of her effort. “Can’t you see it’s really too small?”

Follow us only on Lee Daily for more news like this.