I’ve had what I’ve been calling in private a “poetry block” for a few years now. I can barely read poetry, I can’t write it, and it’s hard to understand anything about it. I used to live for poetry, and I still sometimes teach it to make a living. It’s a strange feeling that I don’t think I’ve ever had before, but it’s in an unusual place: to feel about an entire form the way I’ve often felt about crushes, romantic or sexual relationships, and even relationships.

I was too close to it, and then I couldn’t stand it. It reminded me of a strong feeling I could no longer access, so I wanted it out of my sight. Reading Keats’s Odes by Anahid Nersessian: In this situation, A Lover’s Discourse was like meeting someone new after a long time apart. It gave me a giddy feeling of connection and brought back some possibilities.

I’ll admit that I’m not like most people when it comes to poetry. For most people, poetry is boring or embarrassing. People who write it often feel like they have to take a defensive tone to fight against the idea that it is too much and embarrassing. Teenagers are often associated with poetry: In 2016, Ben Lerner wrote in The Hatred of Poetry: “If you are an adult foolish enough to tell another adult that you are (still!) a poet, they will often describe for you their falling away from poetry: I wrote it in high school; I dabbled in college. Almost never do they write it now.”

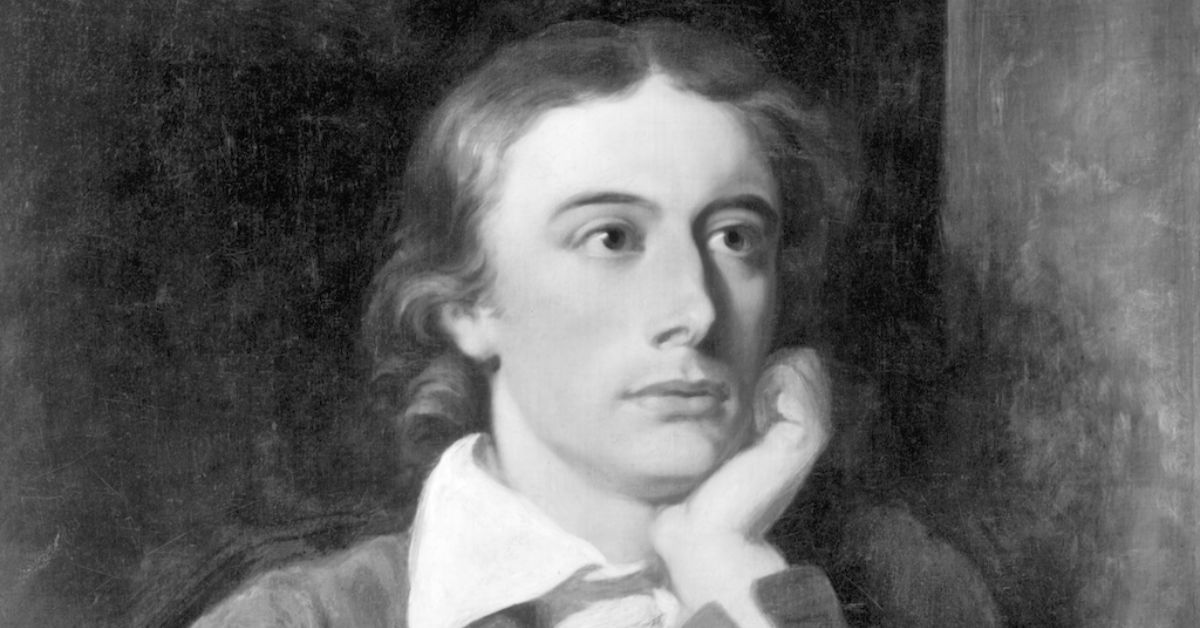

John Keats, a Romantic poet who was born in London in 1795 and died at the age of 25 from tuberculosis, is one of the most famous examples of teens who didn’t want to be numb to the world. People remember him as a delicate, sensitive person who never quite grew up. His contemporaries, like William Wordsworth and Lord Byron, called his work “unhealthy” or made fun of it by calling it “mental masturbation” (“John’s piss-a-bed poetry” was another of Byron’s nicknames).

Piss-a-Bed Keats

Nersessian takes on this reputation head-on, pointing out that it was partly due to his social class (W. B. Yeats called him “the coarse-bred son of a livery stable-keeper”) and to the fact that he was friends with “well-known radicals.” In fact, Nersessian doesn’t apologize for Keats at all, and she makes it clear in the book’s introduction that it’s not for people who still need to be convinced of the worth of the poems it’s about:

“If you’ve never read anything about Keats’s odes before, this book shouldn’t be your first stop.” Nersessian disagrees with the idea that poetry needs to be explained, so she starts a close reading project to show that her subject is not a tired cliché of Romantic escape, but rather an intensely political way to interact with and describe the world.

The Keats in this book is “famously lovable” not because of his genius but because of his “damage.” Anecdotes paint a picture of a troubled boy who was “always in extremes,” a teenager who cared for his dying mother, and a short kid whose “penchant” was not for poetry but for fighting.

Even though he stopped fighting in the end, Nersessian says that his emotionally intense poems are a continuation of an old “hunt for nooks where impassioned and prolonged feelings of all kinds could linger and intensify, private worlds that are not really private.”

This is something that many people who read and write about Keats agree with, but this reading is different because it says that these “unruly” feelings are a test of what it might mean to be “truly free.” In this way, Keats’s Odes picks up where Nersessian’s last book, The Calamity Form, left off by reading the poems as texts that Karl Marx would have liked.

She does this by following George Bernard Shaw’s idea that we can find a “full-blooded modern revolutionary” in the poetry of John Keats (indeed, in his letters, Keats both defended the French Revolution and insisted that England was long overdue its own).

“If Karl Marx can be imagined writing a poem instead of a treatise on Capital,” Shaw wrote in 1921, “he would have written Isabella.” “Isabella; or the Pot of Basil” was written in 1818. It is a long story poem that is based on an Italian story from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron from the 1400s. Isabella, who is “rich from ancestral goods,” falls in love with Lorenzo, one of her brother’s workers, instead of the nobleman her family wants her to marry.

You Can Check Out Latest News:

- Lauren London Talks About The Awkward First Time She Met Jonah Hill

- Chris Perez, Selena Quintanilla’s Husband, Shares A Photo Of Them That Has Never Been Seen Before

When her secret is found out, family and property work together to make sure Lorenzo is killed. Isabella’s lover’s ghost tells her this in a dream, so she digs up his body and buries his head in a pot of basil, which she cares for while crying and pining until she “dies forlorn.”

It’s easy to see “Isabella” as a Marxist poem, since it spends multiple stanzas talking about how Isabella’s family got rich through exploitation: “For them, many a weary hand did swelt / In torched mines and noisy factories”; “For them, the Ceylon diver held his breath / And went all naked to the hungry shark.” What Nersessian does, which is to take Shaw’s statement and apply it to the odes, is harder.

To do this, she uses a quote from “Private Property and Communism” from 1844: “The development of the five senses is the work of all of human history up to the present.” Marx says that the end of private property will lead to the “complete emancipation of all human senses,” since it is only through the end of private property that “these senses and traits have become, both subjectively and objectively, human.” “The eye” can only become “a human eye” in this way.

When you look at it this way, Keats becomes a thinker who is similar to Marx, though in a very different way: a writer who is “also concerned with the distortion of all aspects of human life under capital.” Keats’s dedication to Negative Capability, a term he made up, which Nersessian defines as the artist’s ability to “enter fully into the psychic and sensual orbit of other beings” like a chameleon, can be seen as an application of a Marxist principle: human nature is communal nature, and systems of exploitation and misuse hurt everyone.

Nersessian’s interpretation of Keats gives us many gifts, but one of the most important is the realization that to truly love is to be open to the world, despite and because of its great pain. If reading this book made me feel like I had a romantic connection with someone after a long time without one, it’s worth digging deeper into that feeling. Keats, after all, is both a Romantic poet with a capital R and a writer whose poems and letters to his fiancee, Fanny Brawne, are deeply connected to the idea of “love poetry.”